LAND AND POETICS SHAPING A FEMININE TYPE OF ARCHITECTURE.

Interview with Cazú Zegers.

Words by María D. Martínez.

In 1912, US architect Marian Lucy Mahony, apart from being the second woman receiving her title from the MIT, she built a new concept across modern urbanism’s history together with her husband Burley Griffin: the design of the city of Canberra, capital of Australia, leading the notion that a modern civilisation has to live in sync with nature. It doesn´t come as a surprise that historians left her out of the picture when addressing the project.

Now, the profile of a genuine type of architecture that follows feminine values propels the industry thanks to unique voices like Cazú Zeger’s. Philosophy, poetry, highly conceptual arguments, art and sustainability shape the strong architectural vision of the Chilean.

TERRITORIO Y PALABRA POÉTICA PARA UNA ARQUITECTURA EN FEMENINO.

Entrevista a Cazú Zegers

Texto de María D. Martinez

En 1912, la arquitecta estadounidense Marian Lucy Mahony, además de ser la segunda mujer que recibía su título de Arquitectura en el MIT, trazaba un nuevo concepto en la historia del urbanismo moderno junto con su marido Burley Griffin: el diseño de la ciudad de Canberra, capital de Australia, abanderando la idea de que una civilización moderna debe vivir en sintonía con la naturaleza. No es una sorpresa: los historiadores la dejaron fuera del proyecto a ojos del resto del mundo.

Ahora, el perfil de una arquitectura con valores y cualidades femeninas cobra sentido y se impulsa en la industria gracias a voces como la de Cazú Zegers. Filosofía, poesía, grandes dosis conceptuales, arte y sostenibilidad dan forma al conglomerado de pilares que sustentan el potente concepto arquitectónico de la chilena.

Portrait of Cazú Zegers. Photography: Pedro Quintana. | Retrato Cazú Zegers. Fotografía Pedro Quintana.

M.D.: IN 2016 YOU RECEIVED THE HONORABLE MENTION AT THE ARCVISION AWARDS WHICH RECOGNISE WOMEN IN THE FIELD OF ARCHITECTURE. THEY WERE EVEN REFERRED TO AS “THE FEMALE PRITZKER’S”. DO YOU BELIEVE IT IS ACTUALLY NECESSARY TO CREATE A SPECIFIC AWARD TO APPRECIATE THE ROLE OF WOMEN IN THE INDUSTRY?

C.Z.: I actually don’t think there has to be a different category within architecture such as “female architecture”. Architecture doesn’t have gender. But I do think the Awards have done a remarkable job in giving visibility to women in the industry, and that is highly appreciated.

That reminds me of Arthur Rimbaud and the second letter to his brother in A Season in Hell. There he underlines how annoying the poets of his time were, those who he considered to have sold themselves to the system and to have abandoned their role as “visionaries”. In the text, he mentions that such types of poets will only exist when women abandon the constant servitude to men and free themselves from their chains. Women will be the ones who will create the unfathomed and the inconceivable, men will simply attend and celebrate.

I think that time has come, and it is an emergency to balance human development, leaving out this competitive, cumulative and extractive desire which comes directly from the masculine aspects of being. This is why we need to rebalance, learn to join in, to bring stability, to be respectful, to recover sacredness. Attributes I understand as feminine, not as an opposition to masculine, since there is no real gender in being, in fact we all have feminine and masculine attributes.

It is urgent to reconnect and balance both aspects, since the planet won’t resist other way. The human species have become the real virus for the planet. For me, the COVID pandemic is the antibody the Earth has created against our insensitivity.

M.D.: YOU PLACE YOUR PROJECTS AND YOUR VISION OF ARCHITECTURE WITHIN THE FRAME OF GEOPOETICS. THIS CONCEPT, ALMOST PHILOSOPHICAL, DOES SEEM DIFFICULT TO UNDERSTAND A PRIORI. HOW WOULD YOU DESCRIBE IT IN A MORE COLLOQUIAL WAY? WHAT IS THE ACTUAL GOAL OF THIS WAY OF CREATING?

C.Z.: That question goes straight to the point!

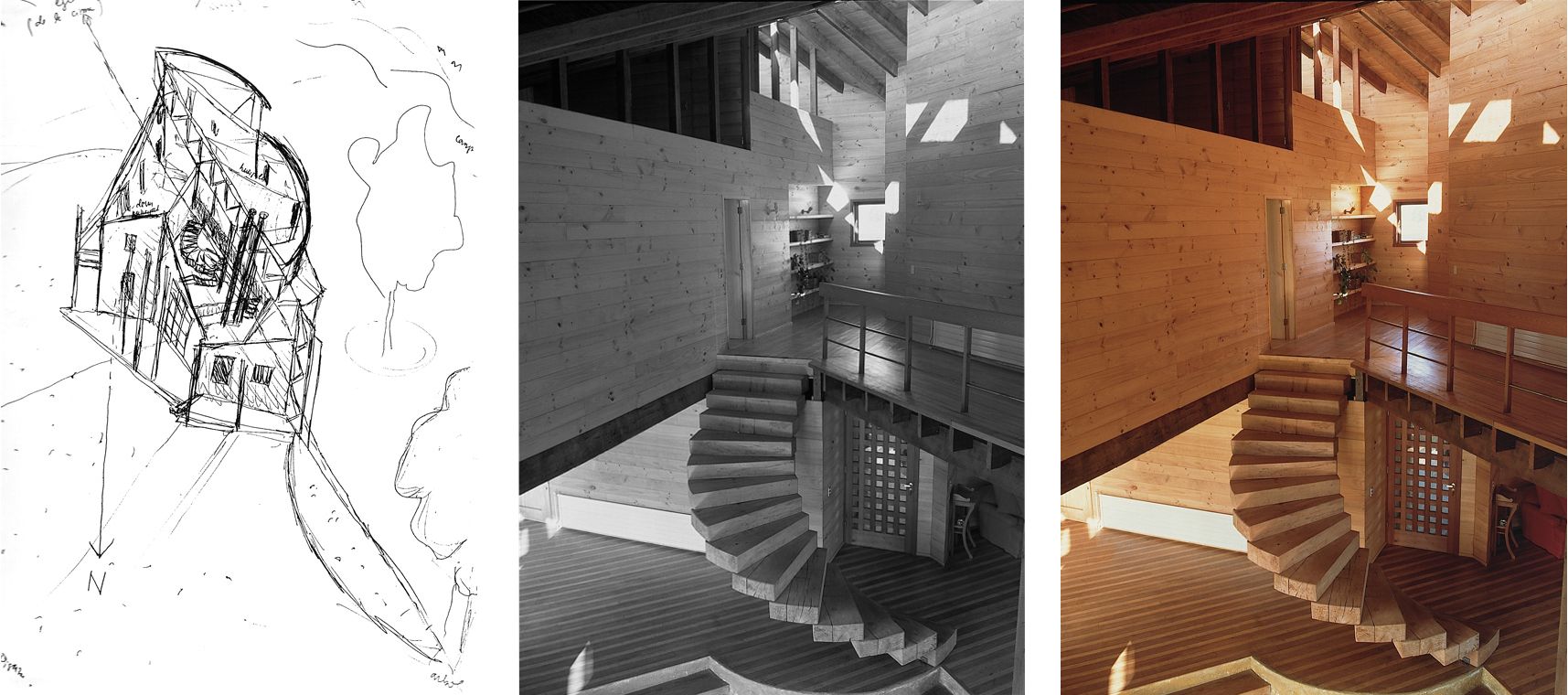

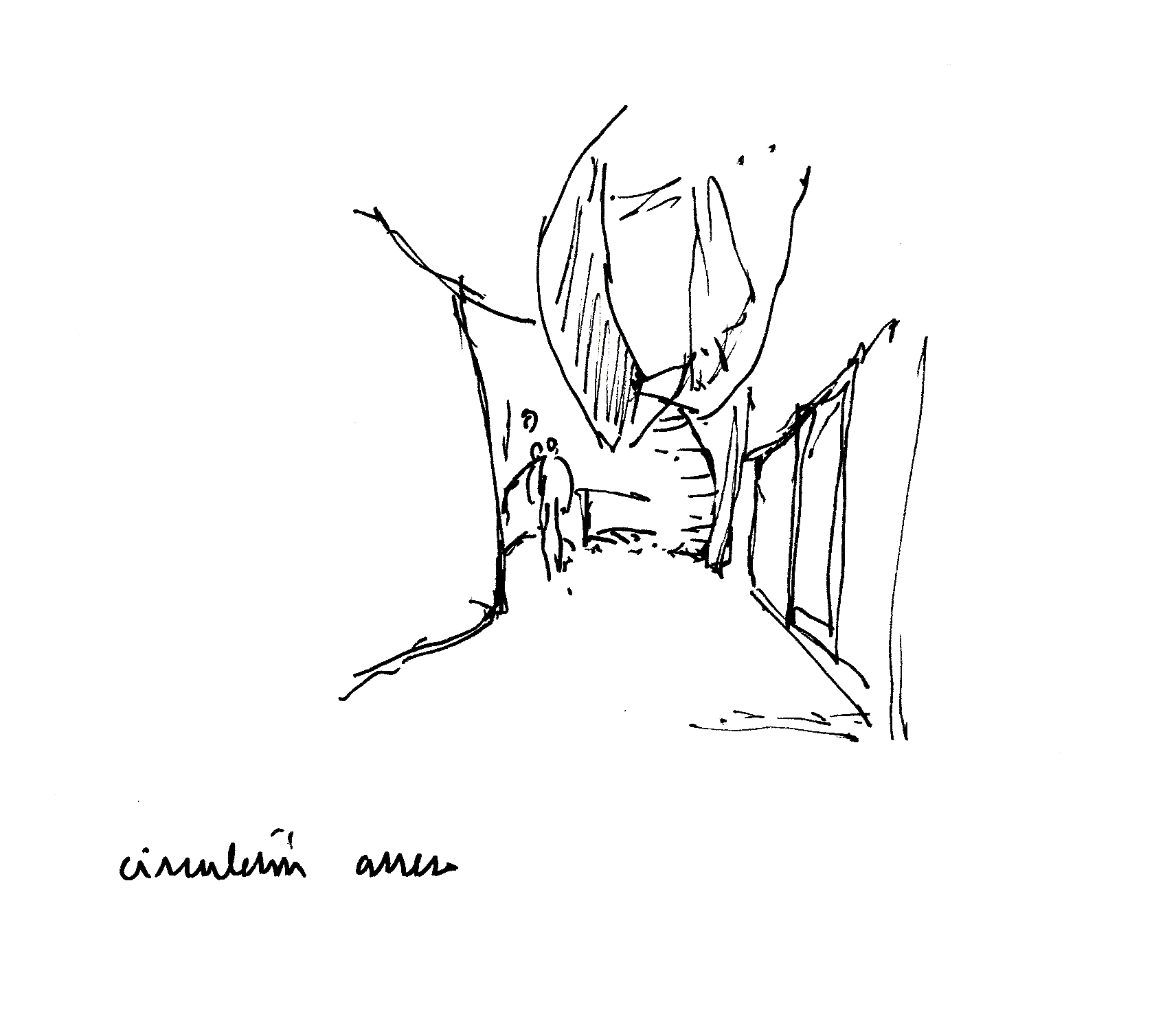

Geopoetry is a concept created by writer Keneth White in 1979. The concept was presented to me by a friend architect: Juan Pablo Almarza. But, actually, it had already been extensively developed by my teacher, the poet Godofredo Iommi, one of the founders of Amereida (Images 1 y 2). He based his concept on the famous words of German poet Friedrich Höderling: “Full of merits, but it is poetically how a man inhabits this earth” (VI, 25). This is also one of the statements that philosopher Martin Heidegger uses in his essay on Art and Poetry. In it, he talks about the origins of the work of art and the meaning of giving and assigning names in a poetic way.

So, in a “more colloquial” way, for me Höderling’s words talk about the creative potential of every human being. We all have within us that creative / spiritual condition, where naming gives things a way of “being”. The etymology of the word “poetry” comes from the Greek mosaic, poesis in Latin language. In Greek it means “the characteristics of the action of doing” and it refers to transforming thoughts into substance. For me it means that when you give something a name you are providing it with a real form of “being”. Following this line of thought, Geopoetry can be understood as the crossroads between land and words. In my case, between land and poetic-words.

Image 1 | Imagen 1

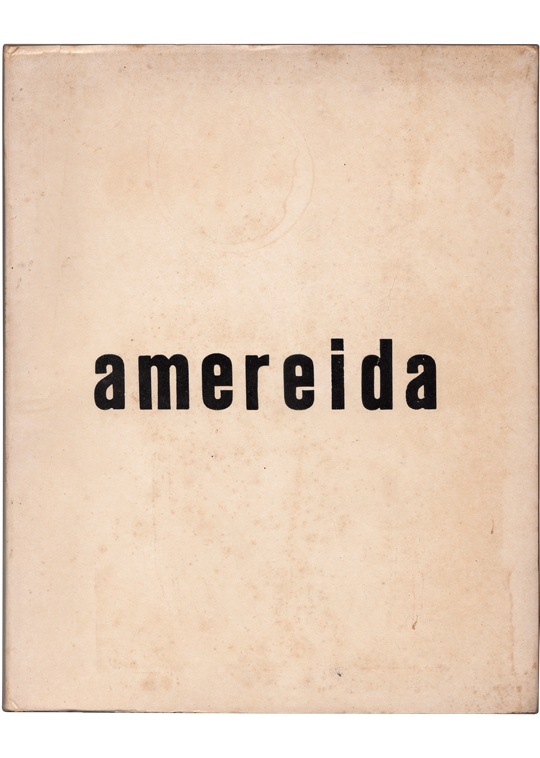

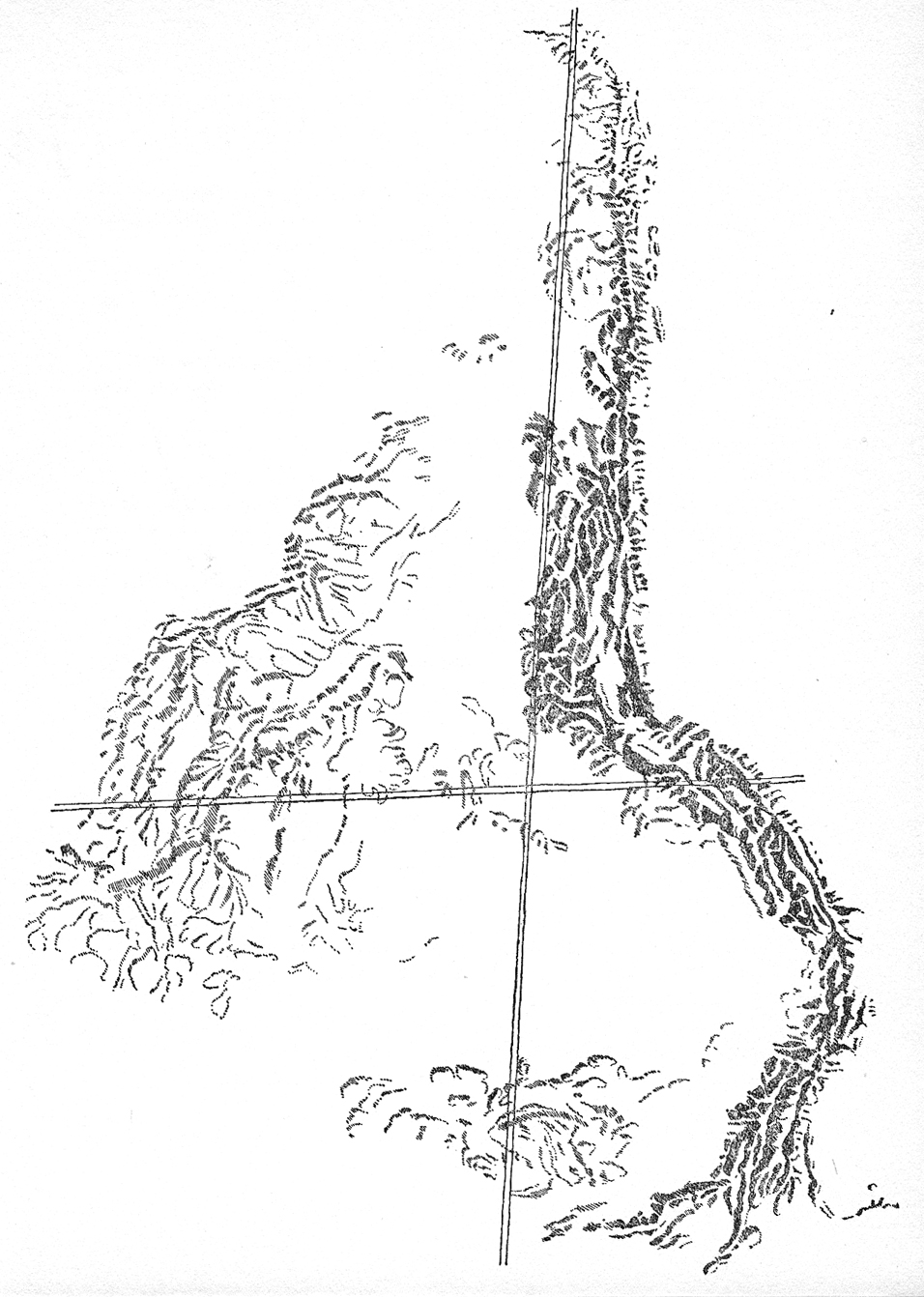

Image 1: Cover of Amereida, Volume One, May 15th, 1967. Source: Tesis de Amereida.

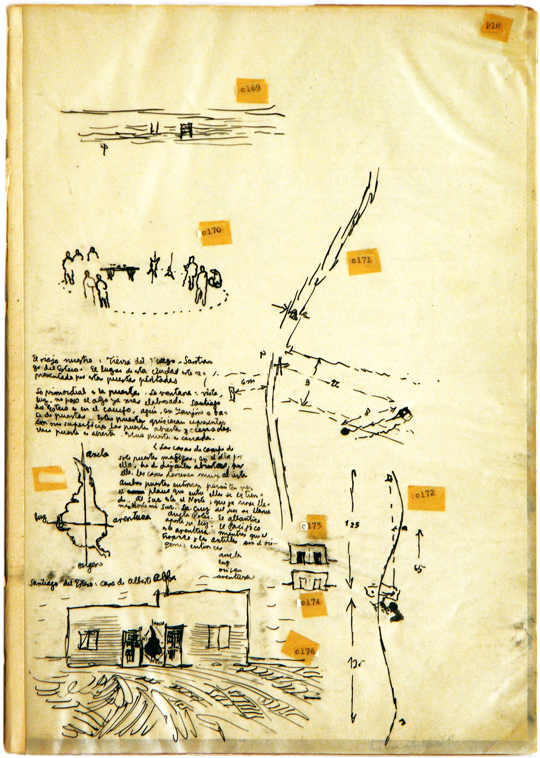

Image 2: Santiago del Estero, Alberto Alba’s house; Alberto Cruz’s notebook p. 18; Amereida’s Trip 1965. Source: Historical Archive José Vial Armstrong © Escuela de Arquitectura y Diseño, Pontificia Universidad Católica de Valparaíso.

*Amereida, or the American Aeneid, is an epic poem that brings together the discovery of America and the Latin adventure of the Aeneid. It comes from the trip made by a group of poets, architects, designers, sculptors, philosophers and artists in 1965. As they travelled across the South American continent, from Tierra del Fuego to Santa Cruz de la Sierra in Bolivia, they wondered about the meaning of America, to then come to understand the purpose behind Amereida´s poem as a way of living and being American.

To give shape to the actual book, various texts, annotations, poems, letters, clippings and drawings of the group were compiled.

M.D.: YOUR THESIS “LIVING LIGHTLY AND PRECARIOUSLY” (HABITAR LEVE Y PRECARIO) BECOMES, IN YOUR OWN WORDS, “AN ARTISTIC PROPOSAL FROM LATIN AMERICA TO THE WORLD”. WHAT’S BEHIND THIS CONCEPT? WHAT IS LATIN AMERICA, AND CHILE IN PARTICULAR, SHOUTING TO THE REST OF THE WORLD WITH THIS PROPOSITION?

C.Z: (Audio). Living lightly and precariously speaks of a relationship, it is the way in which we relate and inhabit our territory and landscape. Based on Amereida’s thesis, it is suggested that America is a continent that “emerges as a gift”, as Columbus had been looking for India and he didn’t recognise it was a new continent when he arrived.

Amereida is an epic-foundational poem in which, emulating the Aeneid, it tells us to be in charge of our destiny and to build a new culture. This is so as not to continue imitating others, or to carry on with the nostalgia of a lost homeland, or to look for a different territory where to “recreate America”.

This means we need to create a new culture, to which I add: a new culture that inhabits almost without leaving a trace on the territory. Because “the land is to America what monuments are to Europe”. I came out with this premise in my first international talk at COARC in Barcelona, for the centenary of Gaudí.

“Living lightly and precariously” comes from living with what it’s at hand, generated by local processes, creating identity associated to the territory. In the words of naturalist Sergio Elortegui, professor at Andes Workshop, it’s a “bio-geopoetic” way of living.

It is a way of building through low technology and with a highly experiential involvement where “precarious” doesn’t mean poor but virtuous. And “light” comes from adding to the great natural monuments, not from imposing ourselves on them. This position was very clear to the original population of Latin America. So, honestly, I think it is the salvation of our planet, to return to a balance between men and environment, with technology serving us and not the other way round.

|

M. D.: EN 2016 SE TE OTORGABA MENCIÓN HONORÍFICA EN LOS PREMIOS ARCVISION QUE RECONOCEN A LA ARQUITECTURA DE EXCELENCIA EN MUJERES. SE LES LLEGÓ A DENOMINAR «LOS PRITZKER EN FEMENINO». ¿CREES QUE ES REALMENTE NECESARIA LA CREACIÓN DE UNOS PREMIOS ESPECÍFICOS PARA VALORAR EL PAPEL DE LA MUJER EN LA ARQUITECTURA?

C. Z.: La verdad es que no creo que deba existir una categoría distinta de arquitectura como arquitectura en femenino, ya que la arquitectura no tiene género. Pero sí creo que el premio ha hecho una labor notable en dar visibilidad a las mujeres en el campo de la arquitectura, y esto es muy valioso.

No puedo no mencionar la segunda carta de Arthur Rimbaud a su hermano en la obra Una temporada en el Infierno. Ahí subraya lo hostigado de los poetas de su tiempo, los que él considera que se han vendido al sistema y han abandonado su rol de hacerse «videntes» para abrir las puertas a lo desconocido que le toca a su tiempo. En ella dice que sólo existirán tales tipos de poetas cuando la mujer abandone el infinito servilismo al hombre y se libere de estas cadenas. Que ellas serán quienes darán paso a cosas insondables a las que ellos, los hombres, asistirán y también celebrarán.

Creo que ese tiempo ha llegado y es de emergencia para equilibrar el desarrollo humano, este afán competitivo, acumulativo y extractivo, que viene de los aspectos masculinos del ser. Por eso mismo necesitamos buscar un balance en la vida, aprender a sumarnos, dar contención, ser respetuoso, recuperar la sacralidad. Atributos que yo entiendo como propios de lo femenino, sin hablar de una oposición entre femenino y masculino, ya que en el ser no existe sexo, todos tenemos atributos femeninos y masculinos.

Es urgente reconectar y dar balance a ambos aspectos, ya que el planeta no resiste más de la otra forma. La especie humana se ha vuelto un virus para el planeta. Para mí la COVID es un anticuerpo de la tierra contra nuestra insensibilidad.

M. D.: SITÚAS TUS PROYECTOS Y VISIÓN DE LA ARQUITECTURA DENTRO DEL MARCO DE LA GEOPOÉTICA. ESTE CONCEPTO QUE ROZA LO FILOSÓFICO PUEDE PARECER DIFICIL DE ENTENDER A PRIORI. ¿CÓMO LO DESCRIBIRÍAS DE MANERA MÁS COLOQUIAL? ¿CUÁL ES EL OBJETIVO DE ESTA FORMA DE CREAR?

C. Z.: ¡La pregunta «directa al hueso»!

Geopoesía es un concepto creado por el escritor Keneth White en 1979. A mí el concepto me lo presentó un amigo arquitecto y colaborador: Juan Pablo Almarza. Pero, a su vez, ya había sido ampliamente desarrollado por mi maestro, el poeta Godofredo Iommi, uno de los fundadores de Amereida (Imágenes 1 y 2). Él se basaba en la célebre frase del poeta alemán Friedrich Höderling: «Pleno de méritos, pero es poéticamente como habita el hombre esta tierra» (VI, 25). Esta es también una de las frases que conforma una de las 5 palabras guía con las cuales el filósofo Martin Heidegger construye su ensayo Arte y poesía. En él habla sobre el origen de la obra de arte y el sentido que tiene el nombrar de forma poética.

Por tanto, de manera «más coloquial», para mí la célebre frase de Höderling habla sobre el potencial creador de todo ser humano. Todos traemos con nosotros esa condición creadora/espiritual, donde el nombrar le otorga «ser» a las cosas. La etimología de la palabra poesía proviene del griego mosaic, en latín poesis. En griego quiere decir cualidades de la acción del hacer, y se refiere a convertir pensamientos en materia. Para mí significa que, cuando uno nombra, le otorga «ser» a las cosas. Siguiendo esta línea de pensamiento, geopoesía se puede entender como el cruce entre territorio y palabra. En mi caso, entre territorio y palabra poética.

Image 2 | Imagen 2

Imagen 1: Portada de Amereida, Volumen Primero, 15 mayo 1967. Fuente: Tesis de Amereida.

Imagen 2: Santiago del Estero, casa de Alberto Alba; Cuaderno de Alberto Cruz p. 18; Travesía de Amereida 1965. Fuente: Archivo Histórico José Vial Armstrong © Escuela de Arquitectura y Diseño, Pontificia Universidad Católica de Valparaíso.

*Amereida, o la Eneida de América es un poema épico que reúne en su nombre el hallazgo de América y la aventura latina de la Eneida. Su origen se encuentra en el viaje realizado por un grupo de poetas, arquitectos, diseñadores, escultores, filósofos y artistas en 1965.

Al recorrer el continente americano desde Tierra del Fuego hacia Santa Cruz de la Sierra en Bolivia, se preguntaron por el sentido de América, para luego comprender y proponer en el poema de Amereida un modo de habitar y ser americanos. Para dar forma al libro se recopilaron textos diversos, anotaciones, poemas, cartas, recortes y dibujos del grupo que formó parte de la travesía.

M. D.: TU TESIS «HABITAR LEVE Y PRECARIO» SE CONVIERTE, EN TUS PROPIAS PALABRAS, EN UNA PROPUESTA DESDE LATINOAMÉRICA AL MUNDO. ¿QUÉ ESCONDE ESTE CONCEPTO? ¿QUÉ ES LO QUE LATINOAMÉRICA, Y CHILE EN CONCRETO, GRITA AL RESTO DEL MUNDO CON ESTA PROPOSICIÓN?

C. Z.: (Audio). El habitar leve y precario habla de una relación, es la forma en la que nos relacionamos y habitamos nuestro territorio y paisaje. A partir de la tesis de Amereida se plantea que América es un continente que «emerge como un regalo», porque Colón venía buscando las Indias y no lo reconoció como un nuevo continente.

Amereida es un poema épico fundacional en el que, emulando a la Eneida, nos llama a hacernos cargo de nuestro destino y construir una nueva cultura. Esto es para no seguir siendo imitadores de otras, o continuar con la nostalgia de la patria perdida, o buscar otro territorio donde «hacerse la América».

A esta llamada a la construcción de una nueva cultura, yo agrego: una cultura que habita casi sin dejar huella sobre el territorio. Porque «el territorio es a América lo que los monumentos son a Europa». Esta frase se me ocurrió en mi primera charla internacional, en el COARC de Barcelona, para el centenario de Gaudí.

El «habitar leve y precario» se crea a partir de habitar con lo que se tiene a mano, lo que generan los procesos locales, creando identidad asociada al territorio. En palabras del naturalista Sergio Elortegui, profesor de Andes Workshop, es un habitar Bio-geopoético.

Esta es una manera de construir en baja tecnología y con una alta experiencia vivencial, donde precario no significa pobre, sino virtuoso. Y leve porque frente a los grandes monumentos naturales uno se suma, no se impone. Esta postura era clarísima para los habitantes originarios de Latinoamérica. Por lo que, honestamente, creo que es la salvación de nuestro planeta el volver a este vínculo de balance entre hombre y medioambiente, con la tecnología al servicio del ser y no al revés, siendo tiranizados por ella.

Audio: Listen to Cazú Zegers talking about her thesis “living lightly and precariously” and how this becomes an artistic proposition from Latin America to the world.

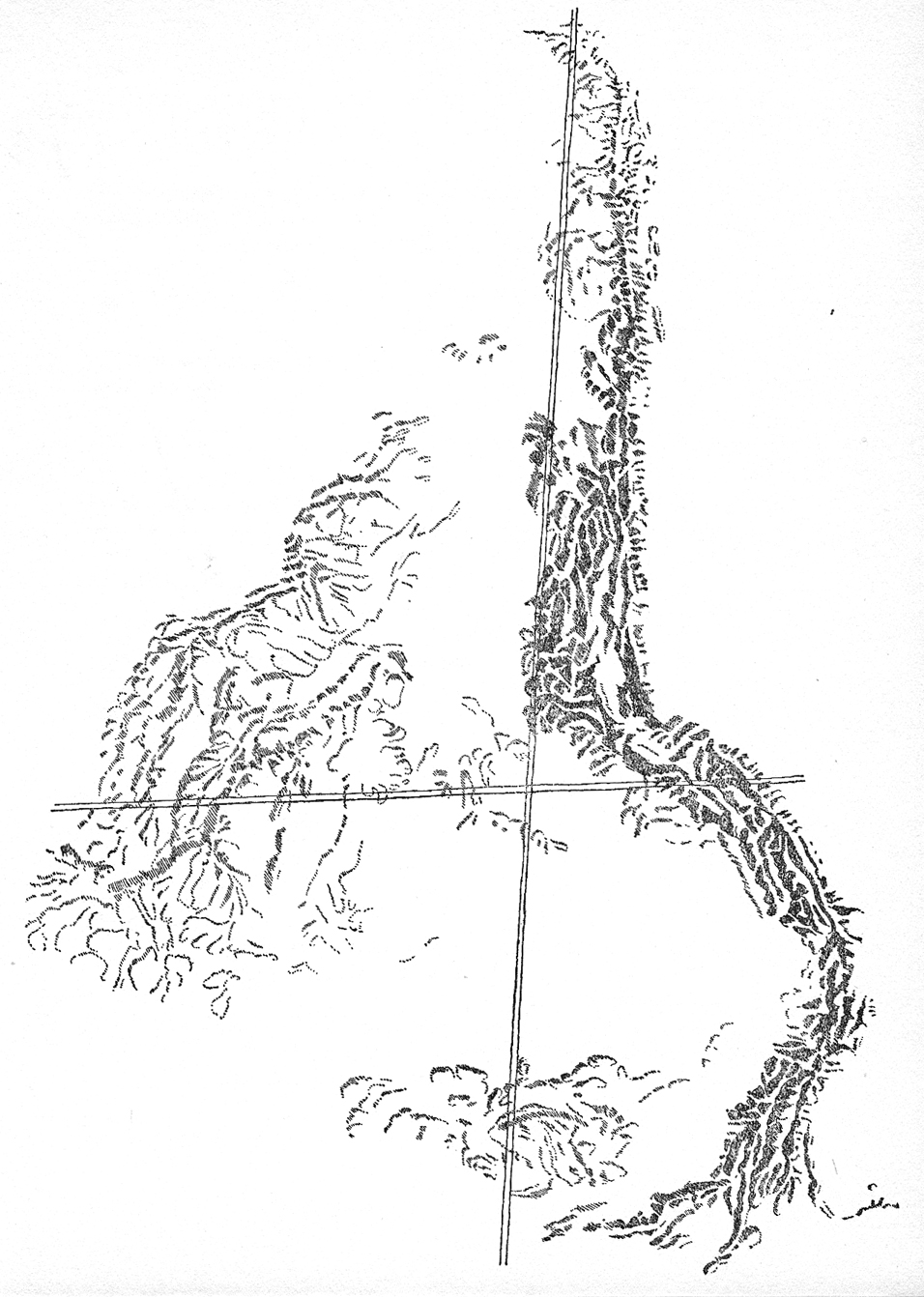

“Latin America has something to say to the world”. Drawing of Inverted America. Source: Tesis de Amereida.

M.D.: FOLLOWING THE ABOVE, COULD YOU TELL US ABOUT THE PROJECT BEHIND THE FOUNDATION AND CENTRE OF GEOPOETIC STUDIES “OBSERVATORIO DE LASTARRIA” AND HOW IT RELAUNCHED AS “FUNDACIÓN +1000)?

C.Z.: At the beginning of the 1980s, while I was studying architecture, I took three off-road motorcycle trips through Chile during my holidays. Those were 3 years in which I travelled Chile from continental end to end, through the mountains, the valley and the coast. In the 1980s Chile was still a vernacular, pre-development country, before the hydroelectric factories and the highway that connects Patagonia to the rest of continental Chile were created. This experience of touring Chile on a motorcycle, the precariousness of the trip where one barely takes a pair of clothing, a tent, and a couple of tanks of petrol, allowed me to deeply experience the territory. I always say that “the territory, the land got into my body / I am territory now”. This gave me a deep understanding of what is like to inhabit this place called Chile.

At the beginning of 2000 I had to return to continental Patagonia, and I was overwhelmed with the inability of the Chileans to understand the true value and identity of our country. This led me to try and open the eyes of political leaders, to try and influence in territorial planning. However, it was too early in time so my ideas were left as a great utopia. That utopian dream inherited from Godo (my professor) of what would happen if we were to leave Chile “underdeveloped” in order to dedicate ourselves to the creation of a natural reserve for the planet.

This dream led me to set up some encounters with friend artists and philosophers. We called ourselves: “Las novedades de la punta del cerro” (The news of the “get the hell out” group), because of the many times they told us to “get the hell out” with our ideas.

After a while, a relative of mine, Álvaro Flaño Amado, told me he had recently restored a large house from the early 20th century in Lastarrias (a patrimonial neighbourhood in Santiago de Chile), and asked me if I had any ideas of what to do with the place. I told him about our group of friends and how fascinating it would be to give a “home” to all the thoughts and projects we had in mind. At that time, we happened to meet the columnist Miguel Laborde and we decided to set up the “Observatorio de Lastarria” foundation at that house Álvaro had renovated, the Casa de Lastarrias. Miguel found out that the house was actually built by one of the architects from “Los Diez” (“The Ten”) an artistic movement from the beginning of the 20th century inspired by the same ideas of identity that inspired us as well.

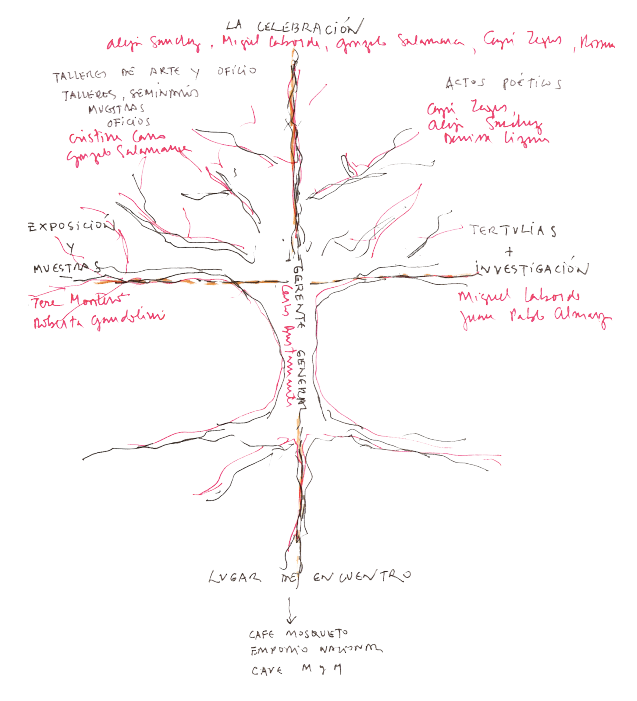

Together with this group of friends, we founded the “Observatorio” based on three premises: What is Chile? Who are Chileans? What type of country do we want to build? And with this, the aim of the project would be built around geopoetry (Image 3). The investigation would be sustained across: territory, poetry, and the endemic products that come from this relationship (we used wine, due to its “mystical/spiritual” aspects, and it seemed to us that it was what spoke best about our identity). We spent five years doing all kinds of cultural activities around these three premises.

Image 3: Foundation sketch with concepts to structure the geopoetic idea behind “Observatorio de Lastarria”. Source: Observatorio de Lastarria, sketch by Cazú Zegers.

In 2010, we decided to leave the building at “Casa de Lastarrias” for different reasons. The foundation continued to operate from an office at my architecture studio, but we were not longer hosting events and at the end of 2012 we decided it was time to put the project on hold until a new willpower arrived.

As an anecdote, what happened is that one day Georges Amar, Keneth White’s colleague from the Institute of Geopoetics, arrived at the “Observatorio”. He was surprised to find a place in Chile that was actually an Institute of Geopoetic Studies. That’s how we got connected to White himself.

The Institute of Geopoetics used to have an annual conference with all the associated institutes. So in 2014 I participated with a talk “Araucanía Capital City” (that name was Miguel’s idea, referencing the work I was carrying out with indigenous communities in the region of Araucanía). When I was presenting at that talk, which was quite successful, I realised I was stating the problem but that it was necessary to get involved and to start working under the motto of: “if you don´t like how things are, get to work and create better practices”. This tell us that we are all actually responsible and part of a place, community, country, territory, a planet. Later on, this assumption is what constituted the starting point for other projects like Pehuenche Route, Andes Workshop, or Santiago Capital Outdoor.

It was with this last project that I met the architect and athlete Canuto Errazuriz. With him, and thanks to his partner, we decided to create a new foundation. So that’s how the “Obsevatorio” evolved into the actual “Fundación +1000”, carrying on with the same initial ideas while amplifying the vision.

M.D.: WHAT ARE THE FUTURE PLANS OF YOUR STUDY TO KEEP SUPPORTING THIS TYPE OF ARCHITECTURE THAT IS KIND AND LOVING TO THE ENVIRONMENT?

C.Z.: We are really going for it and have managed to put together an agile, collaborative, transdisciplinary and “light” team. Just like a Tesla car. We are a “light and precarious” team that’s highly efficient and works freely and in a sustainable way.

Another professor of mine, Alberto Cruz Covarrubias (co-founder of Amereida and the School of Architecture) used to say that “one becomes an architect after 20 years of experience”. My study is now 30 years old and it is now when I feel prepared to answer these questions in a lucid, expanded-vision manner. We are now running lots of projects that are key to new ways of doing architecture and achieving balance.

At the moment we are creating an investigation centre called “Madera LAB” (Wood LAB), taking the concept of British architect Alex de Ritchter, who claims that “technified wood is the new concrete and the 21st century key material due to its environmental credentials”, among other characteristics.

M.D.: THE CONTRIBUTION OF WHICH OTHER FELLOW ARCHITECTS WOULD YOU HIGHLIGHT? ANY VISION YOU REALLY ADMIRE?

C.Z: That’s a tough question! I admire many people, I’m nurtured by many thoughts, I don’t want to name any in case I leave others out. But we all have something to contribute with and that is why I learn from everyone and from all disciplines. I believe the future is transdisciplinarity and collaborative systems.

So, to try and answer the question, scholars I’ve been directly influenced by would be: the school of thought from Godofredo Iommi, Manuel Casanueva, Amereida’s Thesis, Art and Poetry, Zaha Hadid, Paul Virilio, quantum physics, sacred geometry, the work of Lemi Ponifasio and lately Byung- Chul Han. The truth is I know I’m still leaving many out.

M.D.: SO, TO GIVE AN END TO OUR CHAT, WHICH OF THE MANY PROJECTS YOU’VE DEVELOPED IS THE ONE THAT IS STILL CLOSE TO YOUR HEART?

C.Z: I keep a special memory from each one, each of them has been a “Prototype in the Territory” (the title given to the monographic book published by ARQ, 2008) that has allowed me to make this deep reflection on inhabiting and building the world.

Starting with my first house, CALA house (Image 4), which I give the name of “thesis house” since that is when I started creating with this methodology of gesture, figure, shapes; in order to achieve a unique work that talks to the place where it has been built, it gives the place a way of “being”.

The questions raised by the CALA house are answered in full with Tierra Patagonia Hotel (Image 5), a project built through all these ideas on geopoetics and inhabiting a land in a loving way.

Image 4: CALA House. Sketch Cazú Zegers | Photography Cristina Alemparte.

“My thesis house starts from the observation, then the form and the word intersect to create a new, vernacular language, where the disassembling of the traditional shed is the defoliation of the flower. The house is located in the highest part of the land, between the emptiness of the lake and the serenity of the undulating countryside.”

Audio: Escucha a Cazú Zegers hablar sobre su tesis «leve y precario» y cómo esta se convierte en una postura artística desde Latinoamérica hacia el mundo.

«Latinoamérica tiene algo que decirle al mundo». Dibujo de América Invertida. Fuente: Tesis de Amereida.

M. D.: SIGUIENDO EN ESTA LÍNEA, ¿NOS PODRÍAS CONTAR CÓMO SURGIÓ Y CUÁL ES EL OBJETIVO DEL PROYECTO DE LA FUNDACIÓN Y CENTRO DE ESTUDIOS GEOPOÉTICOS «OBSERVATORIO DE LASTARRIA» Y SU REFUNDACIÓN EN «FUNDACIÓN +1000»?

C. Z.: A principios de los años 80, mientras estudiaba Arquitectura, hice tres viajes en moto off road por Chile durante mis vacaciones. Fueron 3 años en los que recorrí Chile de extremo a extremo continental por la cordillera, el valle y la costa. En los 80, Chile era aún un país vernáculo, pre-desarrollo, antes de las centrales hidroeléctricas y la gran carretera que conectó la Patagonia con el resto de Chile continental. Esta experiencia de recorrer Chile con la precariedad de la moto off road –donde apenas se lleva una muda de ropa, una «carpa» (tienda de campaña), un par de bidones de «bencina» (gasolina) y ya– me permitió experimentar el territorio en el cuerpo. Siempre digo que se me metió en el cuerpo / yo soy territorio. Esto me dio una comprensión profunda de lo que es habitar en este lugar llamado Chile.

A principios del 2000, me tocó volver a la Patagonia continental y me abrumó ver la incapacidad que teníamos los chilenos de comprender el verdadero valor y la identidad de nuestro país. Esto me llevó a tratar de abrir los ojos de los líderes políticos, tratar de influir en las planificaciones territoriales. Sin embargo, era demasiado pronto para este concepto y mis ideas quedaban «dando bote» como una gran utopía. Ese sueño utópico heredado de Godo (mi maestro) era un: qué pasaría si dejamos Chile en el «subdesarrollo» para dedicarnos a crear una reserva natural para el planeta.

Este sueño me llevó a armar breves encuentros con amigos artistas y pensadores, quienes nos autonombramos «Las novedades de la punta del cerro» , por la cantidad de veces que, en palabras coloquiales, nos mandaron a la punta del cerro con nuestras ideas.

En esto estaba cuando un familiar mío, Álvaro Flaño Amado, quien recientemente había restaurado una casona de principios de siglo xx ubicada en Lastarrias (barrio fundacional y patrimonial de Santiago de Chile), me preguntó que qué se me ocurría hacer a mí con el lugar. Yo le conté sobre nuestro grupo y lo fascinante de que este pensamiento tuviera una «casa». En ese momento coincidimos con el cronista urbano Miguel Laborde y formamos la fundación «Observatorio de Lastarria» en el enclave de la Casa de Lastarrias. Miguel descubrió también que la casona del Observatorio fue creada por uno de los arquitectos pertenecientes al grupo de Los Diez, movimiento artístico de principios del siglo xx, inspirados en las mismas ideas de identidad que nos inspiraron a nosotros.

Y junto a este grupo de amigos colaboradores fundamos el observatorio con base en 3 preguntas: ¿qué es Chile?, ¿quiénes somos los chilenos?, ¿qué país queremos construir? Y la reflexión del Observatorio se haría en torno a la geopoesía (Imagen 3). La investigación sería cultural basándose en tres columnas vertebrales: territorio, poesía y los productos endémicos que nacen de esta relación (nosotros usamos el vino, por sus aspectos místico-espirituales, y nos parecía que era lo que mejor hablaba de esta relación identitaria). Estuvimos cinco años haciendo todo tipo de actividades culturales en torno a estas tres preguntas.

Image 3 | Imagen 3

Imagen 3: Boceto conceptual para la idea geopoética que sustenta el proyecto del «Observatorio de Lastarria». Fuente: Observatorio de Lastarria, boceto de Cazú Zegers.

En el 2010, decidimos dejar la Casa de Lastarrias por diferentes razones y cerramos este ciclo. Seguíamos operando con una oficina en mi estudio de arquitectura, pero ya no hacíamos eventos y a finales del 2012 decidimos dejar la fundación en pausa, hasta que llegara un nuevo espíritu.

Como anécdota, lo que pasó es que un día llegó Georges Amar, colaborador de Keneth White, y se sorprendió de que en Chile existiera un Centro de Estudios Geopoéticos, lo que nos conectó con el Institute of Geopoetics y con el mismo White.

El Institute of Geopoetics hacía un encuentro anual de todos los centros asociados, por lo que el 2014 me tocó participar con la charla Araucanía Capital City (el nombre fue idea de Miguel a propósito del trabajo que yo estaba llevando a cabo con comunidades indígenas de la región de Araucanía). Al hacer mi presentación, que fue extraordinariamente bien recibida, me di cuenta de que estaba enunciando el problema y que era necesario involucrarse y ponerse a trabajar bajo la premisa: «Si no te gusta el estado de las cosas, ponte a trabajar para crear mejores prácticas». Con este pensamiento estoy diciendo que todos somos actores y responsables de un lugar, comunidad, país, territorio, planeta. De aquí nacen después los proyectos de la Ruta Pehuenche en Araucanía, el Andes Workshop y, por último, el Santiago Capital Outdoor.

Con este último proyecto conocí al arquitecto/deportista Canuto Errazuriz, con quien decidimos –inspirados por su socio– hacer de este último proyecto una fundación para gestionarlo, y así es como la «Fundación Observatorio» se refundó en la actual «Fundación +1000», continuando y ampliando nuestra visión.

M. D.: ¿CUÁLES SON LOS PLANES DE FUTURO DEL ESTUDIO PARA SEGUIR CON LA REIVINDICACIÓN DE UNA ARQUITECTURA «AMABLE» CON EL MEDIO?

C. Z.: Estamos con toda la fuerza y hemos logrado armar un equipo ágil, colaborativo, transdisciplinar y leve como un «auto (coche) Tesla». Es decir, un equipo leve y precario pero altamente eficiente que nos permite trabajar de forma sostenible y libre.

Mi otro profesor, maestro y guía Alberto Cruz Covarrubias (co-fundador de Amereida y la Escuela de Arquitectura) decía que uno recién es arquitecto a los 20 años de ejercicio del oficio. Mi estudio hoy cumple 30 años de trayectoria y realmente es ahora cuando puedo contestar estas preguntas tan lúcidas con una mirada ampliada. Estamos gestionando muchos proyectos que abren nuevas maneras de hacer arquitectura, construir mundo y equilibrar.

Ahora estamos sumando un centro de investigación que hemos llamado Madera LAB, tomando el concepto del arquitecto inglés Alex de Ritchter, quien sostiene que la madera tecnificada es el nuevo hormigón y el material del siglo xxi por sus credenciales medioambientales, entre otros atributos.

M. D.: ¿LA APORTACIÓN DE QUÉ OTROS COMPAÑEROS ARQUITECTOS DESTACARÍAS? ¿ALGUNA VISIÓN QUE TE LLAME REALMENTE LA ATENCIÓN?

C. Z.: Uf, ¡difícil pregunta! Admiro a mucha gente, me nutro de muchos pensamientos, no quiero nombrar unos porque dejo otros fuera, pero todos tenemos algo que aportar y es por eso que aprendo de todos y de todas las disciplinas. Creo que el futuro está en la transdisciplinariedad y los sistemas colaborativos.

Intentando responder a la pregunta, pensamientos y obra que me han influenciado directamente serían: el pensamiento de Godofredo Iommi, Manuel Casanueva, la tesis de Amereida, Arte y poesía, Zaha Hadid, Paul Virilio, la física cuántica, la geometría sagrada, el pensamiento y obra de Lemi Ponifasio y, últimamente, Byung- Chul Han. La verdad es que aún estoy dejando fuera a muchos.

M. D.: PARA TERMINAR, ¿A CUÁL DE TODOS LOS PROYECTOS LANZADOS HASTA LA FECHA LE SIGUES GUARDANDO ESE CARIÑO MÁS ESPECIAL?

C. Z.: Tengo un amor especial por cada uno, porque cada uno ha sido un Prototipo en el Territorio (título bajo el que publiqué los proyectos con la editorial ARQ en 2008), que me ha permitido hacer esta reflexión profunda sobre el habitar y construir mundo.

Partiendo por mi primera casa, la Casa CALA (Imagen 4), a la que nombro como mi casa tesis, porque es ahí donde comencé creando con esta metodología del gesto, figura, forma. Para así lograr una obra original que dialoga con el espacio.

Las preguntas o el camino que se abrió con la Casa CALA concluye en el Hotel Tierra Patagonia (Imagen 5), como la tesis construida de todas estas ideas de la geopoética y del habitar un territorio de forma amorosa.

Imagen 4: La Casa CALA. Boceto Cazú Zegers | Fotografía Cristina Alemparte.

«Mi casa tesis es fruto de la observación, se cruza la forma y la palabra para crear un lenguaje del aquí, vernáculo, donde el desarme del galón tradicional es el deshoje de la flor. La casa se ubica en la parte más alta del terreno, entre el vacío del lago y la serenidad del campo ondulante».

Image 5 |Imagen 5

Image 5: Tierra Patagonia Hotel. Photography Addison Jones.

“The gesture of the building arises from the shapes drawn by the wind, a natural element characteristic of the area. The form seeks not to break into the metaphysical landscape of the place, but to join. The image of the hotel is that of an ancient fossil of some prehistoric animal, stranded on the shore of the lake.”

Then, my own place, SOPLO house (Image 6 | 7), opens the way to novelty.

As of today, and after meeting the choreographer, dancer and theatrical director Lemi Ponifasio (with whom I collaborated artistically), I understood that architecture is a connection of systems across space and around the “emptiness” of a land.

This can be the emptiness of a stage, the emptiness that sustains the different parts of a house, or the emptiness surrounding the territory; but architecture is always born from a relationship. The relationship we create as humans, bonds and acts which architecture gives shape in a material or an intangible way; from a small cabin to a whole territory like the mountain buttress of Santiago. It is not about building a container to live in, but about creating shapes from our relationships with the environment.

Image 6: SOPLO House. Sketch Cazú Zegers

Image 7: SOPLO House. Photography Isabel Fernández

“The breeze (soplo) doesn’t have doors nor windows, it follows the relieves of the valley that surrounds the condor. The steps created walls, language trails, concrete clouds that raise the house from the Manquehue hill. Its concave crystals bring the city to the parlour. Housing attached to Cazú, Clara and other residents, a feminine and democratic form of art. This is the valley of female liberation, flexible spaces, enlargement of the soul without walls or restrictions.”

Imagen 5: Hotel Tierra Patagonia. Fotografía Addison Jones.

«El gesto del edificio surge de las formas que dibuja el viento, elemento natural característico de la zona. La forma busca no irrumpir en el paisaje metafísico del lugar, sino sumarse. La imagen del hotel es la de un antiguo fósil de algún animal prehistórico, varado en la orilla del lago.»

Luego, mi propia casa, la Casa SOPLO (Imagen 6 | 7), «hace la bisagra» a lo nuevo.

A día de hoy, y tras mi encuentro con el coreógrafo, bailarín y director teatral Lemi Ponifasio (con quien me tocó colaborar artísticamente), comprendí que la arquitectura es una conexión de sistemas en el espacio en torno a un «vacío» o un territorio.

Esto puede ser el vacío oscuro de un escenario, o el vacío que sostiene las partes de una vivienda, o el vacío en torno a un territorio, pero la arquitectura siempre nace de una relación. Una relación que generamos las personas, los vínculos y los actos a los que la arquitectura da cabida de forma material e inmaterial, desde una pequeña cabaña a un territorio como el contrafuerte cordillerano de Santiago. No se trata de armar un contenedor para habitarlo, sino de dar forma a partir de las relaciones con el espacio.

Image 7 | Imagen 7

Imagen 6: La Casa SOPLO. Boceto Cazú Zegers.

Imagen 7: La Casa SOPLO. Fotografía Isabel Fernández.

«El soplo no tiene puertas ni ventanas, sigue los relieves de un valle que ronda el cóndor. Los pasos crearon muros, estelas de lenguaje, nubes de hormigón que elevan la casa del Manquehue. Sus cristales cóncavos traen la ciudad a su estar. Vivienda ceñida al baile de Cazú, Clara y otros moradores, un arte femenino y democrático. Este es el valle de la liberación femenina, espacios flexibles, ensanche del alma sin muros ni restricciones.»